By Jennifer Heebner, Editor in Chief

John J. Bradshaw’s early interest in minerals paved the way for an education in chemistry and eventual professional immersion into geology, gemology, and gemstone cutting.

A family friend and geologist nurtured the curiosity of a young John J. Bradshaw, supplying him with minerals that piqued his interest in his eventual career—founder of an eponymous cutting firm and co-owner of Coast to Coast Rare Stones.

“He would always bring me a mineral from wherever he was traveling,” recollects the Nashua, N.H.-based cutter. “When I got old enough, I subscribed to the magazine Rock & Gem, more for the rock part, but the more I read, the more intrigued I was with gems, and especially the cutting.”

After obtaining a bachelor’s degree in chemistry, Bradshaw secured more instruction in geology, mineralogy, crystallography, and finally a graduate gemology degree from GIA. His parents were fully supportive, gifting him his first faceting machine as a college graduation gift. “I was hooked,” he says.

Then at a mineral symposium in 1979, he met renowned faceter Art Grant at a display case of gems commonly set into jewelry as well as ones admired more as specimens, such as Fluorite and Cerussite.

“I can still see that case if I close my eyes,” says Bradshaw. “We quickly became friends, and he gave a young cutter some valuable tips. On any given gem, what works for one cutter may or may not work for another. I believe that no matter how long you have been cutting, there is always something new to learn from another cutter. It happened early in my career, and it continues today.”

The Journey Continues

Even with a strong foundation of studies in gems, minerals, and cutting, Bradshaw worked a day job as a chemist, cutting gems on his own time for three years until he mustered the courage to pursue his passion full time.

When he did, another door opened that elevated his status as a gemologist. Two years after receiving his G.G., he was approached by the Harvard Mineralogical Museum in Cambridge, Mass., to serve as part-time Curator of gems.

“My job was to confirm or deny the identification of every gemstone in the collection,” he explains. “This practical work was great experience handling a vast array of gem material. The Harvard position led the way to working with other museums and institutions in the country, including the Smithsonian and the U.S. Department of Justice.”

Eventually, between working for Harvard, cutting gems, and traveling for buying trips or visiting mining areas, Bradshaw made the decision to concentrate solely on cutting or recutting his own material—with one exception: an 86-carat Sphalerite from Mongolia.

“For this particular stone, I broke my own rule about cutting for other people,” he explains about the gem that a friend asked him to work up. “The rough was magnificent and the locality of Mongolia was exceedingly rare for the species.”

Specializing in Rarities

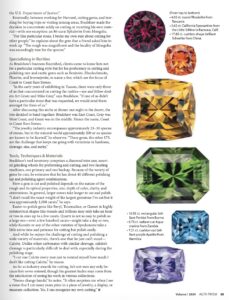

As Bradshaw’s business flourished, clients came to know him not for a particular cutting style but for his proficiency in cutting and polishing rare and exotic gems such as Benitoite, Rhodochrosite, Fluorite, and Jeremejevite, to name a few, which are the focus of Coast to Coast Rare Stones.

“In the early years of exhibiting in Tucson, there were only three of us that concentrated on cutting the rarities—me and fellow dealers Art Grant and Mike Gray,” says Bradshaw. “If one of us didn’t have a particular stone that was requested, we would send them amongst the three of us.”

After discussing this niche at dinner one night in the desert, the trio decided to band together: Bradshaw was East Coast, Gray was West Coast, and Grant was in the middle. Hence the name, Coast to Coast Rare Stones.

“The jewelry industry encompasses approximately 25–30 species of stones, but in the mineral world approximately 200 or so species are known to be faceted,” he observes. “These gems, the other 175, are the challenge that keeps me going with variations in hardness, cleavage, size, and rarity.”

Tools, Techniques & Materials

Bradshaw’s tool inventory comprises a diamond trim saw, assorted grinding wheels for preforming and cutting, and two faceting machines, one primary and one backup. Because of the variety of gems he cuts, he estimates that he has about 40 different polishing lap and polishing agent combinations.

How a gem is cut and polished depends on the nature of the rough and its optical properties, size, depth of color, clarity, and orientations. In general, larger stones take longer to cut and polish. “I don’t recall the exact weight of the largest gemstone I’ve cut but it was approximately 1,000 carats,” he says.

Easier-to-polish gems like Beryl, Tourmaline, or Garnet in highly symmetrical shapes like rounds and trillions may only take an hour or two in sizes up to a few carats. Quartz is not as easy to polish so a large one—over a few hundred carats—might take a day or two, while Kunzite or any of the other varieties of Spodumene take a little extra time and patience for cutting but polish easily.

And while he enjoys the challenge of cutting and polishing a wide variety of materials, there’s one that he just can’t stand—Calcite. Unlike other carbonates with similar cleavage, calcite’s cleavage is particularly difficult to deal with, especially during the polishing stage.

“I cut one Calcite every year just to remind myself how much I don’t like cutting Calcite,” he muses.

As far as industry awards for cutting, he’s not won any only because he’s never entered, though his greatest kudos may come from the satisfaction of seeing his work in various collections.

“Stones change hands,” he notes. “It often surprises me when I see a stone that I cut many years prior in a piece of jewelry, a display, or museum collection. Yes, I can recognize my own cutting.”

Reach Bradshaw at 603-881-7486 or [email protected].

This is proprietary content for AGTA and may not be reproduced.